Evaluating Jewish Schooling During Covid: Alternative Perspectives

This article appeared in the fall 2020 issue of HaYidion, examining how schools are adapting to the challenging circumstances of conducting business during the Covid-19 pandemic.

By Alex Pomson and Nettie Aharon

Thanks to the ubiquity of high-quality cellphone cameras, we’ve all become aware of how different an object is when viewed through a wide-angle lens compared to a telephoto lens. We can play with such differences ourselves. The wide angle brings into view the context and broader landscape in which an object is situated, yet it also loses textures and details, things seen close up. Different lenses yield radically different perspectives, as in the photos below taken from the same point in Yosemite National Park.

This photographic commonplace comes to mind when reflecting on data that our team at Rosov Consulting gathered from day school students about their experience of remote learning since the onset of Covid-19. When we looked exclusively and deeply at data from students in North American high schools, the conclusions we reached were quite different from those prompted by looking at North American data alongside data from schools in Europe and Latin America. The wider context altered everything.

THE STUDY

As part of work with the Government of Israel’s Ministry of Diaspora Affairs, our team was asked to develop a survey for day school students in Europe and Latin America about schooling during Covid-19. The survey explored student access to technology, student satisfaction with the remote learning pedagogies their schools employed, what they felt they gained from this experience, and how Judaic studies and general studies compared when delivered remotely. Five schools in Europe (part of the Educating for Impact network) and two in Buenos Aires (from MaTaCH’s Unit.Ed initiative) took part, with 795 students responding in total.

Subsequently, we were given an opportunity by the Jim Joseph Foundation to explore how high school students in North American day schools experienced this same period. Sixteen schools were recruited to take part, six Community or Conservative high schools and 10 Modern Orthodox schools. 1,383 students participated, all of whom were enrolled in ninth through twelfth grade during the 2019–2020 academic year.

After data analysis was complete, interviews were conducted with school leaders at the schools whose students had responded most positively in order to learn about their educational practices during this period. Findings from the North American study are accessible at Prizmah’s Knowledge Center.

A TELEPHOTO LENS

North American day schools have been praised for the nimbleness with which they responded when schools were required to cease in-person learning. The North American data are consistent with this impression. When asked, “Do you feel that remote learning has set your education back in some way?” a majority (60%) reported that remote learning did not have a particularly notable negative impact on their education.

It is true that a plurality of students (41%) reported they were set back a little, but write-in comments indicate that most students who selected “a little” recognized that while schooling from home was not the same as being physically present in school, they were not badly impacted. Here are some samples:

I found that I continued to understand concepts and I feel comfortable with the topics we studied while online. However, I feel like I missed out on group and hands- on activities that would have been done in class.

I think that in-person learning is far more valuable than remote learning. While I did complete my classes’ curriculum, I think that I would have a better understanding of the concepts if learned in a normal setting.

Those students who felt least badly impacted brought a positive mindset to this experience. This is a strong feature of the write-in responses of those who answered “not at all” to this question; these students found positives even in this most challenging of situations.

It just felt like school came to my house. I still had the same assignments, tests and quizzes, so there was nothing I could complain about. The same things were taught. I could even argue that it boosted my education, because many schools around me were shut down while I was fortunate enough to have class and learn.

I feel that remote learning has given me an opportunity to find myself and discover what kind of person I want to be.

I feel it gave me new skills to have in the future. It was a process getting used to, but I am very glad we had this challenge!

To be clear, even these most positive students recognized that their education had been impacted: 27% in this positive (“not set back at all”) group recognized that they had “learned less remotely compared to when school was in session.” And yet these students also saw a bigger picture: 55% of the students in the “not set back at all” group felt that “remote learning contributed “somewhat” or “very much” to their “being a stronger candidate for the college of [their] choice.” Acknowledging their challenges, they were able to view the experience positively.

GETTING THE JOB DONE

To what extent did remote learning strengthen students’ connection to…

Note: Options included “not at all,” “a little,” “somewhat,” and “very much.” The percentage of students who selected “somewhat” or “very much” are displayed here.

Overall, the impression left by the data from North American students is that their schools competently, even creatively, carried off a challenging maneuver. Of course, it was not perfect, and for most students it was not the same as actually being in school. When students were asked, for example, how much they enjoyed classes on Zoom, how much they enjoyed school projects at home and what they thought of the videos sent home by schools, they indicate that they were neither satisfied nor dissatisfied.

Their responses were consistently three out of five, squarely at the midpoint of a five-point scale. It is as if the students were conveying a sense of “it is what it is.” It could have been better, but it wasn’t bad. This is consistent with the fact that write-in responses indicate that very few students (fewer than 5%) felt their schools let them down during this period. The students recognize and appreciate that their schools got the job done.

A WIDE-ANGLE LENS: BRINGING THE SOCIAL-EMOTIONAL DIMENSIONS OF SCHOOLING INTO VIEW

And yet, there are aspects of the students’ responses that provoke questions, and even concerns, especially when we switch from a telephoto to a wide-angle lens— that is, when we compare responses from day school students in North America with those from elsewhere.

Day school research has rarely explored the experiences of students in different countries. Covid-19 has created such an opportunity. The pandemic’s global reach is terribly dispiriting, but it does have some marginal benefits. For the first time, as far as we are aware, we can compare how day school students—high school students, in this instance—from across the globe respond to the same questions about the Jewish and communal dimensions of their school experience. In doing so, provocative insights surface that touch on the core purposes of day school education, while acknowledging that those insights derive from relatively small samples of students.1

First, and maybe stating the obvious, day school students in North America are generally fortunate in the extent of their access to technologies that enable robust remote learning. Just 5% had to share a device for remote learning with another family member. In Buenos Aires, almost a third did. While 13% of students in North America report having argued during the last week with siblings about access to on- line learning technology at home, more than double that proportion did in the European and Argentinian day schools.

In this sense, North American day school students have access to tools that enable them, individually, to move forward with their education even when sheltering in place. (It’s a sad fact of life in North America that many young people in the general population are not as fortunate as those in Jewish day schools.)

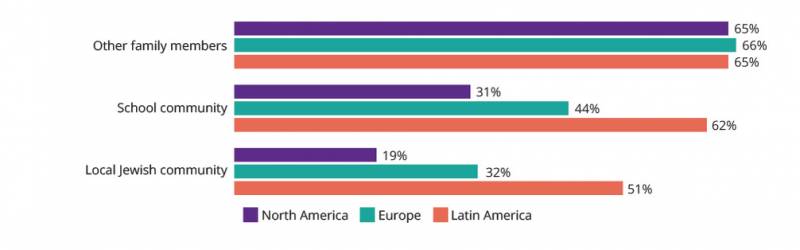

The word “individually” in the last paragraph was not casually chosen. By contrast to day school students elsewhere, those in North America seem to have engaged in remote learning in a somewhat isolated fashion. Asked “To what extent has online learning strengthened your connection to [various entities],” the majority of students, irrespective of location, reported being more strongly connected to “other family members.” However, significantly more European and Argentinian students report a strengthening in their connection to their “school community” and their “local Jewish community” than is the case among North American students.

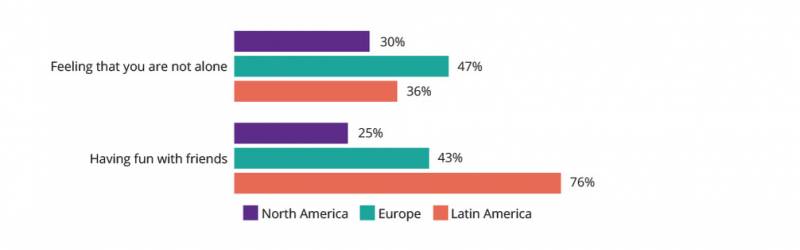

To what extent has online learning contributed to you…

Note: Options included “not at all,” “a little,” “somewhat,” and “very much.” The percentage of students who selected “somewhat” or “very much” are displayed here.

There are similar differences between students’ responses with respect to social-emotional outcomes of remote learning. Significantly more students in Europe and Argentina report that online learning contributed to feeling they were not alone and to having fun with friends. Indeed, these survey items saw some of the greatest differences between students in North America and elsewhere.

SCHOOLS WITH DIFFERENT PURPOSES

Curious about these regional differences, we interviewed senior educators in participating schools in Europe and Latin America to understand the extent to which they had purposely cultivated such outcomes. Strikingly, we did not hear these people talk about particular interventions or programs. What they emphasized was how their schools are organized and to what ends; they drew attention to their priorities and functions. In Buenos Aires, for example, during normal times as well as during the pandemic, a mechanech—a pastoral educator—is assigned to every 50 to 100 students. This educator’s primary role is to support students’ personal, emotional and social development through programs and through ongoing direct contact with students and their families. During the pandemic, this has been profoundly important in keeping students connected and emotionally supported, especially in schools with thousands of students.

In many European and Latin American countries, families have a different relationship to day school than in North America. In Buenos Aires, families choose a school for life, often over the generations. They don’t tend to shop around. And in a highly secular community, schools rather than synagogues serve as centers of community. That’s why a thousand families at a time have attended school Zoom events during the pandemic. In Italy, there were similar themes. Synagogues are important in Milan and Rome (they were formed by different ethnic Jewish immigrant groups), but the Jewish school is perhaps the only place where the whole community comes together, especially in cities where the Jewish community is dispersed. Schools are first and foremost sites of community, and that function has been amplified by the pandemic.

In normal times, a consequence of these patterns is that students can often feel a bit too much at home in school. This is a phenomenon that challenges educators. Students are as likely to come to school to have fun as they are to prepare academically for life after school, especially in Jewish communities where there is a strong culture of going into a family business after school rather than onto college. What were previously seen as difficulties have become sources of social-emotional strength at this most challenging of times.

Finally, there may have been another force shaping student responses, one not created by the schools but by circumstances that have shaped students’ experience of schooling during Covid-19. In Europe, in some of the cities where we gathered data (Madrid, Milan and Rome, for example), Jewish families live in apartments, many without balconies, and were strictly locked down between February and April. School provided the most powerful means by which students could connect with the outside world and with friends. With their cities in acute crisis, school brought fresh air into their homes.

CHALLENGING TIMES PROVOKE ULTIMATE QUESTIONS

North American day schools will never become European, nor should they. They are formed by profoundly different Jewish and civic cultures. They provide a much more intense grounding in Jewish literacy and Jewish life than is typically the case in Europe. And yet these data from other corners of the day school globe offer an intimation of ways in which day schools can more fully serve students and be something else to their families, especially at times of severe social disruption. With these data, a wide-angle vista comes into view of a different kind of day school.

To clarify, we do not see this as a zero- sum game, a straight choice between academic and social-emotional outcomes, between a more collectivist ethos and a more individualistic one. In those North American schools where more students do indicate they have been connected to their school communities during the pandemic (although perhaps not at Latin American levels), the students were also more likely to say that their education had not been set back. While some of these North American schools have drawn on circumstantial advantages that echo those in Europe—they are tight knit, sometimes isolated communities—they have also invested in extracurricular programming that has cultivated a sense of community among their students: some form of daily prayer; town-hall meetings for students; and extra-curricular events such as shelter-in-place color war and a Yom Ha’atzma’ut parade that came to every student’s home. These drew on and developed a powerful sense of intimate community and school spirit, all of which was to the social-emotional and academic benefit of their students.

With schools and students facing the prospect of many more months of uncertainty about how and where education will happen, there is all the more reason for schools to ask themselves whether they are ready to invest more intensively in their community-building functions. The answer to that question depends on the answer to another even more ultimate question: What indeed are Jewish day schools for?

1 Of course, such comparisons are fraught with methodological challenges: Do students understand certain concepts the same way even when framed in their native language; for example, in Budapest, Buenos Aires and the Bay Area do they think of the concept “local Jewish community” in the same way? Do they have the same understanding of survey scales? A four out of five in Madrid might be much less positive than in Manhattan where respondents might be more reluctant to award high scores. If, in Europe, schools tend to be regarded with more respect than in the United States, does that mean Italian students will be less inclined to criticize their teachers than those in the United States? These questions are important to consider when making sense of the data.